I live on the Viejo Sendero Español—the Old Spanish National Historic Trail. The casita I rent is about fifty feet from the road that was part of it, and it has felt significant to me since I moved in. I drive parts of the trail daily to and from the Santa Fe Plaza, where I work at Sorrel Sky Gallery. Santa Fe is the oldest and highest-elevation capital in the United States. It is a historic hub of the southwest, connecting three national historic trails: El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, the Santa Fe Trail, and the Old Spanish Trail. The Old Spanish Trail is an arduous trail of high mountains, deep canyons, and arid desert traversing 2,700 miles from Northern New Mexico to Los Angeles, California. It was used extensively between 1830 and 1850.

Perhaps it feels significant because I need some ancestral healing.

Ancestral healing is one of the themes of Taylor Sheridan's recently concluded Yellowstone series. (I loved 1883 because of Elsa’s narration and beautiful writing.) In his series, which includes 1923, Sheridan is telling a generational story of the West. Ancestral healing is a type of spiritual healing that recognizes that people can inherit trauma from their ancestors, even if they didn't experience it directly. It’s about reconciling with one's ancestors' legacy, including their triumphs and struggles.

Indigenous peoples have deep cultural, spiritual, and ecological connections with their ancestors. These connections are passed down through generations, shaping identities, traditional practices, and a sense of belonging. My ancestry is diluted but complex, like a curry dish with many spices. But little has been passed down through generations. My family chose to keep their secrets secret, including bootlegging, a Catholic orphanage, child abuse, sexual abuse, and more.

Before my ancestors arrived in Plymouth, the Wampanoag had a thriving community. Long before 1540, when the conquistador Don Francisco Vasques de Coronado claimed the "Kingdom of New Mexico" for the Spanish Crown, there were many thriving adobe towns the Spanish called pueblos. These towns had a population of close to 100,000 people, who spoke nine languages and lived in an estimated 70 different multi-story adobe towns.

Don Juan de Onate became the first Governor-General of New Mexico and established his capital in 1598 at San Juan Pueblo, 25 miles north of Santa Fe. When Onate retired, Don Pedro de Peralta was appointed Governor-General in 1609. Peralta and his men laid out the plan for Santa Fe at the base of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the site of the ancient Pueblo Indian ruin of O’Ga P’Ogeh (Tewa for White Shell Water Place). One year later, he moved the capital to present-day Santa Fe.

For seventy years, the Spanish and Franciscan missionaries tried to convert and control the indigenous population. But in 1680, the Indigenous, led by the Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo religious leader, Popé, forced all Spanish residents—along with many Indians from Isleta and Socorro—to leave Nuevo México. They killed 400 colonists and sent the rest retreating down the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro to El Paso, Texas, and Juárez, Chihuahua. They burned all the buildings but the Palace of the Governors, which still stands today. The uprising returned Santa Fe to its original occupants for twelve years.

In 1692, however, under Diego de Vargas, the Spanish army reconquered Nuevo México and recolonized formerly abandoned pueblos and missions. However, there were constant raids and often bloody wars with the Comanches, Apaches, and Navajos, which pressured the Spanish authorities and missionaries to ally with Pueblo Indians and maintain a civil policy of peaceful coexistence (whatever that means). However, the Spanish maintained a closed empire, allowing trade only with the Americans, British, and French until 1821, when Mexico gained its independence from Spain and Santa Fe became the capital of the province of New Mexico.

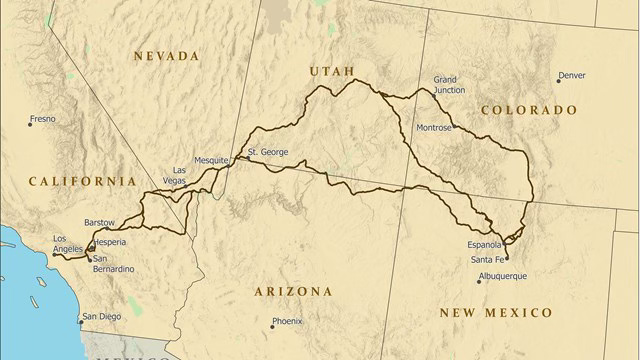

Juan Maria de Rivera explored the Old Spanish Trail, including southwest Colorado and southeast Utah, in 1765. Franciscan missionaries Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante unsuccessfully attempted the trip to California, which was just being settled. They left Santa Fe in 1776 and reached the Great Basin near Utah Lake before returning via what is now Arizona.

After the Mexican Revolution, capitalism and manifest destiny established the Santa Fe Trail when William Becknell left Franklin, Missouri, in 1821 with 21 men and a packed train of goods. Between 1821 and 1880, the Santa Fe Trail was an important commercial trading route connecting Missouri, east of the Mississippi River, with Santa Fe. It also brought thousands of white European invaders or settlers to the West.

The historic Old Spanish Trail was a capitalistic venture. There was money to be made transporting serapes and other woolen goods from New Mexico to Los Angeles, trading for and returning to Santa Fe with California-bred horses and mules. That was the vision of 25-year-old Mexican trader Antonio Armijo, who led the first commercial caravan from Abiquiu, New Mexico, to Los Angeles in late 1829. Mexican and American traders continued to use routes similar to the one he pioneered, frequently trading with Indian tribes along the way. It was from a combination of the indigenous footpaths, early trade and exploration routes, and horse and mule routes that the trail network known collectively as the “Old Spanish Trail” evolved, according to the National Parks Service.

Thanks partly to the Old Spanish Trail, the Santa Fe Trail, and the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, Santa Fe emerged as the overland continental trade network hub linking Mexico and the United States markets. John C. Frémont, ‘The Great Pathfinder,’ took the route, guided by Kit Carson, in 1844 and named it in his report published in 1845. After the United States took control of the Southwest in 1848, other routes to California emerged, a wagon route was opened to southern California, and use of the Old Spanish Trail sharply declined.

I lived for twenty years in Pagosa Springs, Colorado, and frequently stopped at the Spanish Trail marker in the San Luis Valley. Escalante Canyon, named for the missionary above, is between Montrose and Grand Junction, where I have lived. The Old Spanish Trail has been a subtly important part of my life, and I have lived in many places with complicated histories involving white settlers, ranchers versus sheepherders, the Spanish, Mexicans, and Indigenous people.

Santa Fe ‘belonged’ to the indigenous, Spain, Mexico, and the United States. On August 18, 1846, in the early period of the Mexican-American War, an American army general, Stephen Watts Kearny, took Santa Fe and raised the American flag over the Plaza. Two years later, Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ceding New Mexico and California to the United States.

In 1862, after Albuquerque fell to the Confederacy, Major Charles Pyron of the Second Texas Regiment was sent to unprotected Santa Fe and hoisted the Confederate flag over the Palace of the Governors on March 13.

With supplies running low, Confederate Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley was determined to advance on Fort Union to capture its great stores and arsenal. That advance along the Santa Fe Trail resulted in the Battle of Glorieta Pass, a defeat that forced Sibley and his men to retreat south along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. Lacking supplies to continue fighting, they quickly abandoned Santa Fe and Albuquerque. By June 1862, the Confederate forces had retreated to El Paso, never to fight in the West again.

Many don’t know that Civil War battles were fought in the Southwest.

Soon after the Civil War broke out, Confederate political and military leaders hatched a plan for Western conquest. They would raise a force in Texas, march up the Rio Grande (along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro), take Santa Fe, turn northeast on the Santa Fe Trail, capture the federal supplies at Fort Union, head up to Colorado, capture the gold fields, and then turn west to take California. New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado were "giant recruiting grounds" for potential enlistees to the Southern cause. All three states had populations loyal to the Confederacy, and southern New Mexico had already effectively seceded from the government at Santa Fe and formed a separate territory extending all the way to California.”

I have ancestral connections to the Battle of Glorieta Pass. My great, great, great, great grandfather, Father John Kehler, was the chaplain for the First Colorado Regiment of Colorado Volunteers under Colonel John Chivington. He accompanied soldiers to New Mexico. He was not a soldier but served an important role and documented the deaths and the journey in his journal. When his term as chaplain expired, Kehler relocated to Wyoming, where he served as a missionary among the Indians. He was not with the First Colorado Regiment and Chivington in 1864 when they massacred 230 Cheyenne and Arapahoe women, children, and elderly.

I believe Father Kehler had compassion for the Indians. Still, I’m also conflicted that he was a missionary trying to convert them to Episcopalianism, just as the Franciscans did with the Tewa people. Why can we not, as humans, allow others to believe whatever they want and practice their faith? Why do we think our religion is somehow better, the one true path over others? Why do we think we are superior to others based on skin color, country of origin, wealth, education, strength, skill, or ability? These are questions I cannot answer.

I also know little about ancestral healing, but epigenetic DNA research has shown that our DNA changes based on trauma. The trauma experienced by my ancestors is passed down to me via RNA. There is death, war, and loss in all our histories. Some places speak to us, though we know not why. Santa Fe has felt that way to me for many years. I do not understand why. I have no ancestors here that I have found other than Father Kehler’s brief trip to the area with the First Colorado Regiment. I was told we had indigenous bloodlines in our family, but that has not been proven. On my father’s side, we can trace our lineage to one of the first Texas Rangers. Who knows. I may have ancestors who fought for the Confederacy at Glorieta Pass.

Maybe that’s why I can see both sides of a political, cultural, or spiritual argument.

The process for ancestral healing, from what I have read, is similar to all spiritual healing: self-reflection, meditation, breathwork, rituals to honor one’s ancestors, and telling their stories, which are our stories, whether fictional or historic.

I will continue to tell the profound and complex stories of my people. Some I may make up because I can only surmise what happened, but I will be guided by my intuition and the quiet time I spend in communion with them. I know they are there, listening to me now, wanting me to discover who they were and why they did what they did.